13 Mar Coaching as a Leadership Style: The perceived Benefits of a Leader Adopting a Coach Approach Leadership Style.

Thesis for: MBA Advisor: Dr. Jan Austin

Dec , 2016,07:00am EST

Dr. Andriana Eliadis, Executive Education Facilitator at Cornell University, NY, USA and Director at CorporateExecutiveCoach.

Coaching as a Leadership Style: The Perceived Benefits of a Leader Adopting a Coach-

Approach Leadership Style

Capstone project submitted in partial fulfillment of the requirements for the Degree of Master of

Business Administration in Organizational Behavior and Executive Coaching

University of Texas at Dallas

Jan Austin, PhD

December 2016

Coaching as a Leadership Style

DEDICATION

This Capstone project is dedicated initially to my parents, who taught me and “coached” me

in believing that everything is possible and empowered me in every step I made; also to my sister

Roula, who encouraged me to continue my graduate studies and never give up, to my brother Gianni

and Roula, who have been like second parents to me since I was born, and of course to my two

loving daughters, Kalliopi and Marianna, and my husband Christo, who have been patient and

supportive during my educational and academic endeavors. I love you all dearly.

ACKNOWLEDGMENTS

I must thank from the bottom of my heart all my professors who contributed to my academic

development in UTD since March 2015. To Dr. Jan Austin, for her inspiration, patience, genuine

interest, and collaboration to conclude this capstone project; also to my entire cohort, 12B, who

supported me and collaborated so well during really demanding times. Last, to my personal assistant

Sofia, who has been a great support at work, and my financial assistant, Dimitri, who understands

me and takes on responsibilities and initiatives to help alleviate my work load and stress.

You have all inspired me and given me strength to continue.

I am grateful to have met and worked with you all!

A sincere thank you.

Andriana

Chapter 1: Introduction

The stimulus for conducting this study is twofold. Initially it came from the numerous

executives, managers, supervisors, and plain employees, whom I have met these past years through

my collaboration with their companies to conduct corporate training and coaching programs for

them, and from my formal coaching education at University at Texas at Dallas (UTD).

Coaching as a leadership style has been discussed a lot in the recent years in corporations, in

HR departments, and in executive training rooms. Since change is inescapable, leaders have been

trying to find more effective paths to lead and manage their people. My study is focused on the

perceived benefits a leader and his/her people can have if a coach-approach leadership style is

applied. I would like to start by tracking down where the word coach derives from and when it

originated:

The word coach derives from 15th-century Hungary, referring to the village of Kocs, where

fine transportation coaches were first constructed. The purpose of a coach was to transport

people from where they were to where they wanted to go. Similarly, executive coaches

facilitate the transportation of leaders to new levels of development and effectiveness.

(Underhill, McAnally, & Koriath, 2007, p. 7)

In today’s modernized, technological age, with intellectual awareness and international

stimuli all around us, leaders and their teams have the need to feel acknowledged, respected,

rewarded, and valuable within their corporate realms. According to Nohria, Groysberg, and Lee

(2008), in their article, “Employee Motivation: A Powerful Model,” there are four drives that

improve employee motivation. One important drive they discuss is the drive of a bond; they say, “to

engender a strong sense of camaraderie – is to create a culture that promotes teamwork

collaboration, openness, and friendship” (p. 82). Employees need to believe that there is a future for

them and that developmental opportunities exist.

Motivation and inspiration energize people, not by pushing them in the right direction as

control mechanisms do but by satisfying basic human needs for achievement, a sense of

belonging, recognition, self-esteem, a feeling of control over one’s life, and the ability to live

up to one’s ideals. Such feelings touch us deeply and elicit a powerful response. (Kotter, p.

93)

Therefore, when a person feels and believes all the aforementioned, then he/she is happier, more

energized, and more productive within his/her work environment. This outcome can benefit all

stakeholders, first of all the corporation itself, all the leaders entailed, the employees themselves, and

ultimately the clients of this firm. Therefore, this can drive productivity and profitability to rise.

Ultimately, the “perceived benefits” will come back to the same stakeholders from where the

positive corporate climate once began.

The challenge is, for leaders to see the benefits that a coaching leadership approach has and

utilize it to elicit and maximize their results. When employees are not happy within their work

environment, they are more likely to start the “job hunt” for better opportunities. “In general, people

leave their jobs because they don’t like their boss, don’t see opportunities for promotion or growth,

or are offered a better gig (and often higher pay); these reasons have held steady for years” (Harvard

Business Review, 2016, p. 20).

Chapter 2: Problem Description

The goal of this assignment is to discuss and analyze, via various literature and a case study,

the benefits leaders, their organizations, and their people, can have when a coach-approach

leadership style is adopted. When leaders can create “more effective ways to create and sustain

change” (Stober & Grant, 2006, p. 1) for their corporation, they can empower their people, create a

positive corporate culture, increase motivation, and at the same time improve their own leadership

strategies by focusing on the essential leadership issues. This can be attained, by giving ownership

and responsibilities, by delegating effectively, by training and developing others, and by trusting and

respecting their people. According to Cappelli, Singh, Singh, and Useem (2010), in the article,

“Leadership Lessons from India”:

To engage employees, these leaders create a sense of social mission that is central to

company culture, encourage openness by developing and personally modeling systems that

provide transparency, empower employees by enabling communication and pushing decision

making down through the ranks, and invest in training. (p. 1)

It is essential for leaders to recognize the importance of a “coach-like” culture and commit to

spreading it throughout their organization. Manfred F. R. Kets de Vries (2014), in his article,

“Coaching the Toxic Leader,” says, “Senior executives have the power to create an environment that

allows people to grow and give their best – or a toxic workplace where everyone is unhappy”

(p. 102). Thus, adopting a coach-approach leadership style must begin from the senior leaders of an

organization and work its way down to the last employee.

Coaching as a Leadership Style

Chapter 3: Literature Review

As aforementioned, one of the reasons my interest in this topic sparked was from my formal

coaching education at UTD while studying the book, Coaching as a Leadership Style, by Robert F.

Hicks (2014). The book analyses a study conducted primarily for healthcare industry executives, but

its theory is applicable in all business sectors. This book studies how leadership and coaching can

work together to create a better corporate environment where its executives can communicate

effectively and conduct their day-to-day business via better constructive, more open, more

motivating and empowering approaches. As the author states, “A case is made for coaching as a

means to help Elite Professionals make the transition to a team-based, task-interdependent work

environment, and for coaching as a skillset that will help operationalize the components of

transformation leadership” (p. xiii). He has included dialogues and conversations in order to

understand how a coaching conversation can alter the leadership style of an executive and what the

effects of that can be.

Another source of information is the book, Executive Coaching with Backbone and Heart by

Mary Beth O’Neill (2007). In chapter 11 of the book the author describes how leaders can

effectively coach their employees. She discusses possible pitfalls and gives a great explanation of the

path leaders can take to coach their people. She says that bosses should take two distinct roles when

coaching employees: “Role 1: Articulate performance expectations, and ensure that the employee

commits to them. Role 2: Coach and develop the employee to accomplish those expectations” (p.

263). Mary Beth O’Neill argues in her book that when a boss uses coaching effectively, there are

many benefits created that will influence the entire organization. Specifically, she says that once

effective coaching is used, “it has ripple effect throughout the organization”

Coaching as a Leadership Style

(p. 281). This source will be used to show how a leader can use coaching to improve his people’s

performance and relationships within the team and the organization.

In the book, The Psychology of Executive Coaching, the author, Bruce Peltier (2010),

discusses bad and good leader traits. He analyses the habits that can jeopardize a leader’s position

and points out that “poor working relationships and inability to develop or adapt (including

inflexibility)” and “authoritarianism and excessive ambition, insensitivity, aloofness, lack of follow-

through, and inability to do strategic planning” were examined to be characteristics of leaders, in the

United States, “who had fallen by the corporate way-side” (p. 334). He also gives a list of positive

leader traits which all link to coaching as a leadership style.

Dianne R. Stober and Anthony M. Grant (2006), in the book, Evidence Based Coaching,

define coaching by defining its nature and discuss “effective ways to create and sustain change” (p.

1). They give several definitions of what coaching is and establish a core base of what is common to

the definitions they have cited. They say that the common themes:

include a collaborative and egalitarian rather than authoritarian relationship between coach

and coachee; a focus on constructing solutions and goal attainment process, rather than solely

analyzing problems; the assumption that clients do not have clinically significant mental

health problems; an emphasis on collaborative goal setting . . . and is typically directed at

fostering the ongoing self-directed learning and personal growth of the coachee. (p. 3)

Here the editors support the coaching style as an effective means of development and leading. There

are also case scenarios that explain how coaching can make a difference and help various

businessmen and/or businesswomen reach a desired and self-designed goal.

In his article, “What Leaders Really Do”, John P. Kotter (2001) explains what the job of

leaders actual is. He states that, “Leadership . . . is about coping with change” (p. 86). He discusses

Coaching as a Leadership Style

the difference between “motivating people versus controlling and problem solving” (p. 93), and

states that employees can be motivated by being supported by their leaders via coaching, feedback,

role modeling. Thus, coaching helps “people grow professionally and” enhances “their self-esteem”

(p. 93). He claims that successful motivation gives employees the energy to deal with problems and

obstacles and better cope “with the inevitable barriers to change” (p. 93). This concept supports my

topic by linking it to the definition of coaching and to its potential benefits.

Another article that supports a coach-like culture is the article, “Leadership Lessons from

India” (Cappelli et al. 2015). In this article, the authors explain the way leaders in India lead their

people and the success stories behind this leadership style. They say that in order:

to engage employees, these leaders create a sense of social mission that is central to company

culture, encourage openness by developing and personally modeling systems that provide

transparency, empower employees by enabling communication and pushing decision making

down through the ranks, and invest heavily in training. (p. 1)

This article validates the initial premise of this project and supports a coaching leadership style

method. This article discusses how this leadership style has been applied in the real business world

and its positive outcomes.

“Primal Leadership” (Goleman, Boyatzis, & McKee, 2001) analyses an interesting route to

high-level leadership. They study leadership behavior via emotional intelligence and also see it from

a neuroscience perspective. The connection here with coaching is that, according to their findings,

for leaders to tap into their emotional intelligence, there is a five-step process, which “is designed to

rewire the brain toward more emotionally intelligent behaviors” (p. 37). This five-step process is

basically asking themselves five open-ended questions, which will bring awareness of oneself and,

therefore, self-knowledge.

Coaching as a Leadership Style

James Waldrop and Timothy Butler (1996), in their article, “The Executive as Coach”

explain the benefits that a coach approach can have on managers of organizations. They say that

“Good coaching is simply good management. It requires many of the same skills that are critical to

effective management . . . Similarly, the goal coaching is the goal of good management” (p. 110).

The authors of this article analyze which coaching techniques can be used by a manager to become

“more effective” in his/her “new role” (p. 116). They emphasize the importance of organizational

behavior and sate that, “Being an effective coach is one essential part of that key to success” (p.

117).

The article, “Driving Organizational Change with Internal Coaching Programs: Part One,” by

David Roch and Ruth Donde (2008), describes how companies benefit when internal coaches are

used in an organization to promote change management and acquire new skills. “Requiring leaders

to coach ensures their skills are embedded . . . with regular usage of coaching muscles, the opposite

happens – leaders find themselves suddenly applying their coaching skills in new and unexpected

ways” (p. 12). They state that by not giving people the answers and thus helping them to work out

any issues both they develop their people and at the same time leaders are less stressed and have

more time to use for other tasks.

A very interesting investigation is described in the article, “The New Science of Change” by

Christopher Koch, (2006). It proves via scientific and neuroscience methods how the human brain

functions when it faces change and when it is told what to do. Koch states, “The traditional

command-and-control style of management doesn’t lead to permanent changes in behavior. Ordering

people to change and then telling them how to do it fires the prefrontal cortex’s hair-trigger

connection to the amygdala” (p. 1). He comes to the conclusion that asking questions is the best

method managers can use to elicit change and bring solutions. This is a great article that

Coaching as a Leadership Style

scientifically proves that the coaching method of asking questions and being open to responses from

employees can bring optimum results.

Another great article, by Carol Wilson, (2004), “Coaching and Coach Training in the

Workplace,” discusses how companies have evolved from an authoritarian style “towards self-

directed learning . . . companies are moving away from consultancy towards coaching.” (p. 96). She

discusses how “Companies are falling over themselves to provide their senior and middle managers

with personal coaches, and to train them in coaching skills” (p. 96). When a person builds your

confidence, supports you, brings about a new perspective for you, and inspires you, that person

makes a difference in your life. These are “key elements in both coaching and in managing

successful teams in the workplace” (p. 96). Wilson, in this article, also discusses the management

style of the Virgin Records founder, Richard Branson, which as she says “embodied all the

principles currently recognized as effective coaching, although at the time the term in its current

sense had not been invented” (p. 96). The key elements were: ownership, acknowledgment, and

blame-free culture. As history proved, Branson’s management style was effective and benefited both

the employees and the company. “The staff loyalty to the brand was phenomenal, and sales

outstripped predictions year by year . . . Branson’s management style filtered down through the

company” (p. 97), providing an ideal example for all his people to follow. This is a key element that

must be considered when a company desires to adopt a coach-like leadership style; the senior

executives must “lead by example.”

Coaching as a Leadership Style

Chapter 4: Project Description

Methods

This capstone aims to observe how leaders and their corporations, in real-life business

situations, can benefit when applying coaching as a leadership style. Therefore, qualitative methods

are the most appropriate to uncover the perceived benefits of leaders adopting a coach-approach

leadership style. As Yin (2015), says in his book Qualitative Research from Start to Finish:

Qualitative research most of all involves studying the meaning of people’s lives, as

experienced under real-word conditions. People will be performing in their everyday roles or

will have expressed themselves through their own diaries, journals, writing, and photography

− entirely independent of any research inquiry. (p. 9)

As he says, “qualitative research has an array of specialized types or variants” (p. 8); the case-study

method is one of the 12 variants that Yin argues to be “frequently recognized” (p. 8). Thus, a case-

study method has been utilized for this capstone:

As a research method, the case study is used in many situations, to contribute to our

knowledge of individual, group, organizational, social, political, and related phenomena. Not

surprisingly, the case study has been a common research method in psychology, sociology,

political science, anthropology, social work, business, education, nursing, and community

planning. . . . Whatever the field of interest, the distinctive need for case study research arises

out of the desire to understand complex social phenomena. In brief, a case study allows

investigators to focus on a “case” and retain a holistic and real-world perspective—such as in

studying individual life cycles, small group behavior, organizational and managerial

Coaching as a Leadership Style

processes, neighborhood change, school performance, international relations, and the

maturation of industries. (Yin, 2014, p. 4)

Conducting a case study is the most suitable method to explore the aforementioned research

question, as the behavioral events of the sales executive examined in this case study cannot be

controlled by the researcher, and the study is basically examining “how” an executive can lead

effectively via coaching approaches (Yin, 2014). Yin says that:

Doing case study research would be the preferred method, compared to the others, in

situations when (1) the main research questions are “how” or “why” questions; (2) a

researcher has little or no control over behavioral events; and (3) the focus of study is a

contemporary (as opposed to entirely historical) phenomenon. (p. 2)

The case study in this capstone project is examined “in its real-world context” (p. 2) and backed up

with contemporary research and business leadership journals by distinguished scholars in this

business arena.

Skills of the Case-Study Researcher

Case studies have been thought to be “easy” and many social scientists believe that all they

need is to simply “tell it like it is.” “No beliefs could be farther from the truth. In actuality, the

demands of a case study on your intellect, ego, and emotions are far greater than those of any other

research method” (Yin, 2014). The reason for this is that, unlike a laboratory experiment, case study

“data collection procedures are not routinized” (p. 72). Consequently, besides the “technical aspects

of data collection,” there are “ethical dilemmas, such as dealing with sharing of private information

or coping with other possible field conflicts” that “only an alert researcher will be able to take

advantage of unexpected opportunities rather than being trapped by them—while still exercising

sufficient care to avoid potentially biased procedures” (p. 72). Unlike standardized testing, like

Coaching as a Leadership Style

GMATs, GREs, LSATs, or other tests like math or science tests that can assess levels, such as a

person’s knowledge and intellectual capabilities, there is no “test” to measure a person’s ability to

become a good case-study researcher. However, Yin (2014), distinguishes five attributes that a good

case-study researcher should have. They are the ability to:

(1) Ask good questions−and interpret the answers fairly.

(2) Be a good “listener” not trapped by existing ideologies or preconceptions.

(3) Stay adaptive, so that newly encountered situations can be seen as opportunities, not

threats.

(4) Have a firm grasp of the issues being studied, even when in an exploratory mode.

(5) Avoid biases by being sensitive to contrary evidence, also knowing how to conduct

research ethically. (p. 73)

Yin, argues that if any researcher lacks one or more of these attributes, the attributes can be

developed as long as one is “honest in assessing her or his capabilities in the first place” (p. 73).

Subsequently, every researcher must have the ability to acknowledge his/her biases and have the

ability to not judge or create false assumptions, which are rooted in his/her beliefs, but are not part of

the particular case-study phenomena.

The author of this study has extended organizational experience with numerous executives in

the USA and Europe. She has acquired a Bachelor’s degree in Economics and Business

Administration, a Masters Certification in Human Resources Management, and is presently perusing

a Masters of Business Administration (MBA) in Organizational Behavior and Executive Coaching;

also she has received professional coaching training and a professional coach certification (PCC)

from the International Coach Federation (ICF). She has been training and coaching executives in

various business fields for over 10 years. The assumptions that have been formed through her

Coaching as a Leadership Style

education and professional experiences in relation to how executives can lead effectively are the

pivoting points of this study. The author of this study shares the outlook of Austin (2013) in terms of

what some effective traits of leaders are and how they lead. Austin writes in her Ph.D. dissertation:

1. Effective leaders are aware of themselves and others, and they use this awareness to

improve their interactions

2. Effective leaders actively pursue their development as leaders—they are enthusiastic

about coaching and other means to improve

3. Leadership skills are not innate—they can be learned through the active pursuit of

various developmental experiences and sense-making as a result of experiencing

adversity. (p. 68)

Moreover, another basis of this study, as it examines the perceived benefits of a leader

adopting a coach-approach leadership style, is presented by Bungay (2016), who says:

So let’s look at why coaching others helps you. It lets you work less hard and have more

impact. When you build a coaching habit, you can more easily break out of three vicious

circles that plague our workplaces: creating overdependence, getting overwhelmed and

becoming disconnected. (Location Nos. 136–140)

Thus, the executives who have adopted a coach-approach leadership style are leaders who have all

the aforementioned leadership attributes in combination with the perceived benefits, as Bungay

states above.

Coaching as a Leadership Style

Chapter 5: Case Study Profile

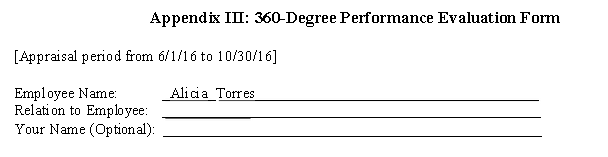

This chapter will provide the case profile of the sales executive receiving corporate training

in management, leadership, business communication skills, and coaching. She is being coached on

how to adopt a coaching leadership style approach toward her team, director, CEO, and her

colleagues in general. The sales executive, who will be given the pseudonym Alicia Torres, to

protect her identity, has been trying to find better means of communication via coaching

methodology to improve her team’s effectiveness, communication, and ultimately, her company’s

profits. A weekly journal was kept by the trainee/coachee, and a copy was given to the corporate

trainer/coach. In addition, a 360-degree assessment was conducted, as agreed, for this leader by her

team and colleagues at the conclusion of her training to determine the progress of this executive. An

empirical investigation is being conducted via coaching and teaching methods to observe and

examine the results that such a method can produce.

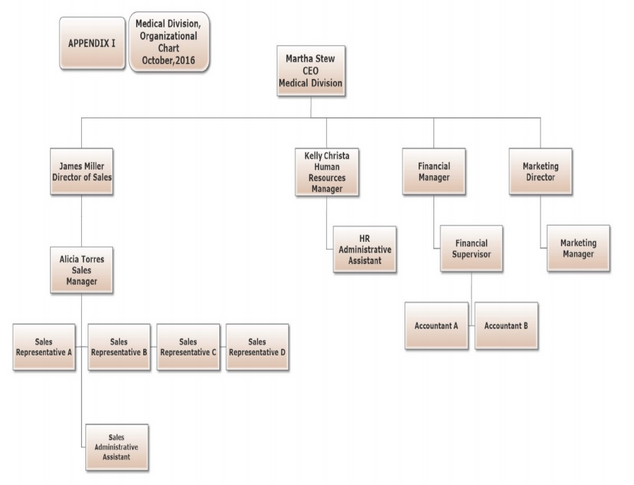

Alicia is a sales manager of an international pharmaceutical company. She had been working

for the company for 15 years when, as the best sales person in her division, she was promoted to

sales manager. She has been a sales manager for 5 years now and supervises a team of four sales

representatives. Alicia reports to the sales director of the company, to whom we will give the

pseudonym JamesMiller. James manages all the sales divisions of the company and he reports

directly to the CEO of the medical sales division, to whom we will give the pseudonym, Martha

Stew. The human resources manager, whom we will call, Kelly Christa, oversees the general

movement of the employees as they are either promoted and/or change departments and/or divisions.

Also, Kelly oversees the training and development sector of her company.

Coaching as a Leadership Style

Although Alicia was an outstanding sales person, as a sales manager, she felt inadequate and

insecure. She had never worked as a manager before and never had the opportunity to become a

team leader or head of a team in the past. Consequently, Alicia requested support from her sales

director, CEO, and human resources manager, to hire an external executive coach to assist her in

improving her managerial skills, her team communication skills, her effectiveness as a sales manager

in general. She hoped through this process to achieve better team sales results and increase the

market share of her company’s products in the long run. As Alicia is a valuable executive to her

company, her request was approved and an executive coach was hired for her, on her company’s

budget. Therefore, about 6 months ago the author of this study was interviewed and hired as Alicia’s

executive trainer and coach.

Coaching as a Leadership Style

Chapter 6: Case Study Analysis

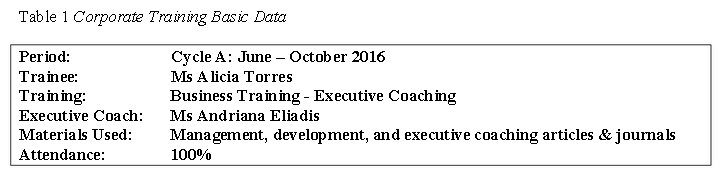

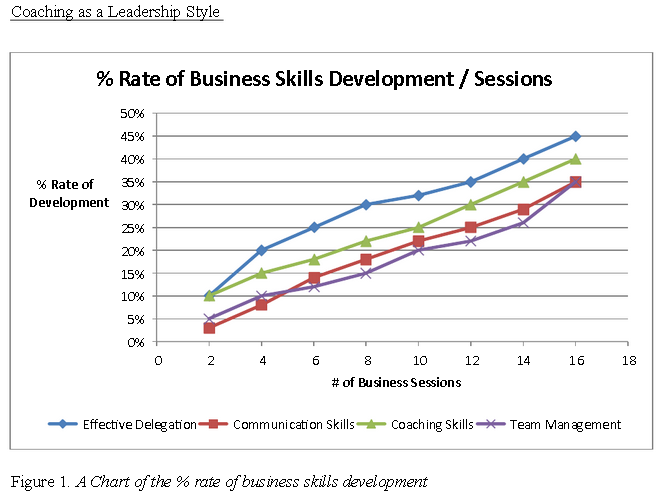

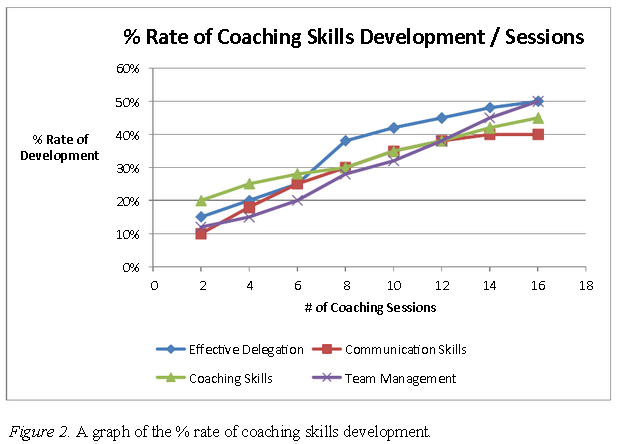

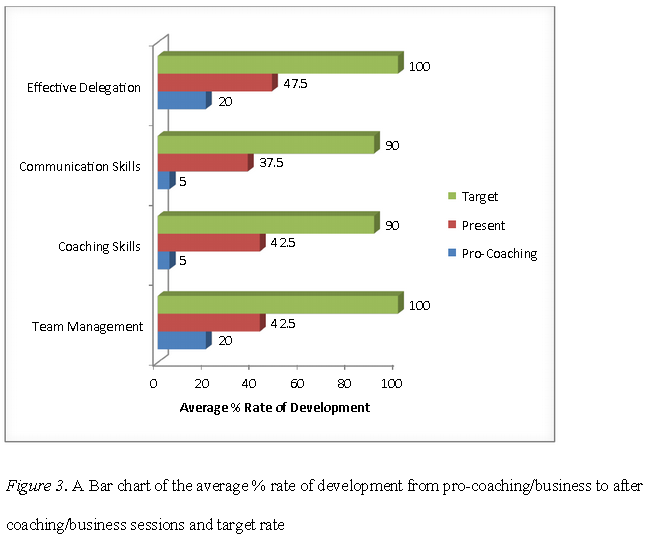

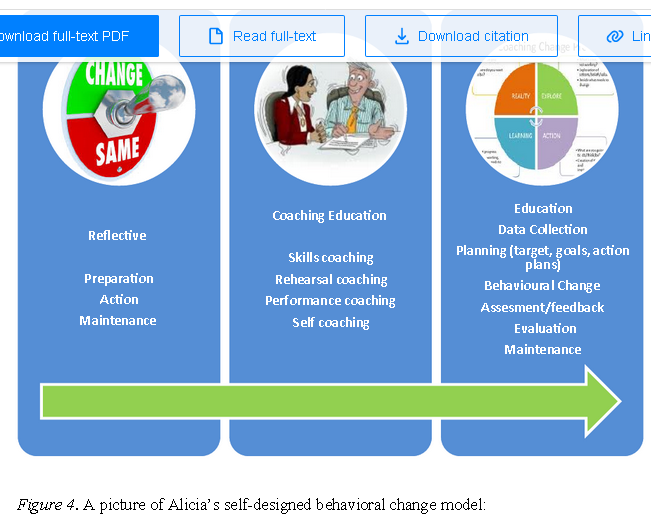

The coaching agreement with the company and Alicia was twofold. Initially, she needed to

learn basic managerial, leadership, communication, and coaching skills. At the same time, she was

being coached to see what works for her, what does not, and how and in what way(s) she can

develop and become an effective sales manager. The ultimate objective of this corporate training

program is a challenging one for Alicia, as she has to reach her full potential—100%–in the arena of

effective delegation and team management, and 90% of her potential in communication and

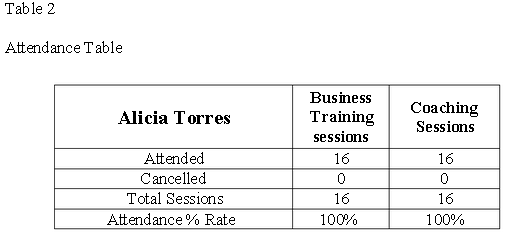

coaching skills. Therefore, it was agreed to design a training program consisting of two training

cycles. Each cycle is comprised of 16 business training sessions and 16 coaching sessions, then, at

the end of each business cycle, a 360-degree assessment is conducted. Alicia’s targets must be

reached by the end of her second training cycle, which will be concluded by the end of July 2017.

The first cycle began in June 2016 and was concluded at the end of October 2016, with a 360-degree

performance appraisal. The second cycle will commence in February 2017 to enable her to reach the

initial target set by both Alicia and her company. The meetings in the first cycle were conducted

both online and/or face-to-face, depending on Alicia’s and her coach’s availability, travels, and so

on. Two 90-minute weekly sessions were set up; one meeting per week was a business training

session and the second a coaching session. The curriculum taught was reviewed by and agreed upon

by all the parties involved—Alicia, James, Martha, and Kelly. The business-training curriculum

included theoretical and practical approaches of general management, team management, leadership,

coaching, emotional intelligence, business communication, and employee developmental skills.

Following is selected data from the compiled report submitted to her company:

Alicia Torres Business Training and Executive Coaching Report

This coaching report provides manager/coach with narrative about the Executive’s

managerial and/or coaching knowledge and effectiveness. It offers developmental feedback to help

the participant(s) professional development.

Sessions Objectives:

The focus of this training is business management skills and executive coaching with Alicia

Torres. Business and Coaching objectives for Alicia include enabling her to:

• Comprehend her managerial, administration style.

• Develop management and coaching skills for current and future assignments in XYZ

company

• Learn the fundamentals of emotional intelligence.

• Develop team management and team organizational skills.

• Develop specific managerial/coaching competencies in accordance with her

company’s and manager’s requirements and feedback.

• Broaden her repertoire of managerial styles in accordance with her company’s

culture, values, and policies.

Cycle A Business Topics Covered:

Management skills

• How good are your management skills?

• Team management skills

• How good are your people skills?

• Management roles

• Common management misconceptions

• Fundamentals of team emotional intelligence

Improving team effectiveness

• Building an effective team

• How does your team work together?

• Improving team effectiveness by analysing daily activity

• Team briefings

• Staying in touch with your team

• Matching tasks to interpersonal skills

• Learning what your people think

• Why rules are there. Helping people understand and enforce rules

• Building confidence in other people

Executive Coaching—Progress to Date

During the training, Alicia held weekly one-on-one business and coaching sessions for the

purpose of discussing and learning effective methods of managing and coaching her team, which

consists of four members.

The coaching objectives that have been targeted thus far have been to:

• Improve her team communication, management, and organization skills.

• Formulate and communicate the roles of each member of her team.

• Use effective delegation to improve projects, task effectiveness and team support.

• Broaden her repertoire of managerial styles, particularly a coaching style that

encourages the long-term development of direct reports

Feedback on Coaching Style

Milestones and feedback:

• Self-evaluation and personal development targets.

• The vision of her team’s role within this company.

• Team communication development and team bonding techniques

During her coaching sessions Alicia worked on her personal management skills and

completed tasks related to team development and communication. She successfully fulfilled her

tasks, which enabled her to commence a more effective communicating pattern with her sales team.

She was able to start recognizing her own roles, the roles of the members of her team, and the

responsibilities those roles entailed. This, permitted her to become a better task delegator and to

initiate managing her team and its projects in a more efficient manner. Alicia has demonstrated

motivation and willingness to try out new skills and behaviors. This was an enlightening and

promising prospect for her, as change starts to take place from within. Clemmer (1999), in his book,

Growing the Distance, says that “Albert Einstein once observed that we can’t solve a problem with

the same type of thinking that created it” (Location No. 1087). In other words, a leader cannot

influence his/her peers to change by using “the same behaviour that contributed to their current

behaviour” (Location No. 1087). Therefore, Alicia, from her training and coaching sessions, has

understood the need to change her behavior and see things differently, so as to be able to positively

influence her team’s effectiveness.

Further on, introduction to the fundamentals of emotional intelligence enabled her to

recognize her weaknesses and begin to design an action plan for her personal improvement. As Kite

and Kay (2012) say in their book, Understanding Emotional Intelligence:

Whether it’s getting on with others, reacting to situations at home or at work or simply

reflecting on life’s purpose, our emotions play a critical part in defining who we are, what we

want to achieve and our effectiveness in managing our routes to success . . . The sign of

intelligent people is their ability to control emotions by the application of reason. Maya

Mannes. (p. 40)

They continue by saying that:

Self-awareness is a requisite of personal competence. Self-awareness can be split into three

parts: emotional self-awareness, accurate self-assessment, and self-confidence. Emotional

self-awareness is acknowledging what you feel about situations and how they affect you.

Accurate self-assessment requires an examination of your own strengths and weaknesses.

Self-confidence is being sure of your own self-worth and what you are capable of achieving.

In order to be able to manage yourself, your emotions and your actions you need to know

yourself.” (pp. 40–41)

When Alicia was introduced to Emotional Intelligence (EQ) literature, and conducting coaching

sessions, she was able to comprehend her own EQ and be more open and prone to listening to her

people and her colleagues in order to increase her engagement with them and improve her team’s

communication quality.

If you are emotionally intelligent, you will be fully aware that all others may not be so. This

means that you must manage their perceptions. This involves a degree of positive

manipulation, an understanding of the psychology of effective communication and a

judicious choice of what you show and say to your audience. (Kite & Kay, 2012, p. 224)

Receiving feedback from her manager(s) and peers and direct reports from her professional

environment was an important facet of her development. Alicia, like many others, has been having

trouble with receiving “negative” or developmental feedback. Alicia discussed this issue in one of

her coaching sessions. She realized that when others gave her negative feedback, she felt

intimidated, resistant to the feedback, perceiving that she was being critiqued, judged, that they were

ungrateful toward her. She ultimately felt anger and disengagement. Clemmer, (1999) says:

Like beauty – or service, quality, honesty, or integrity – leadership is in the eye of the

beholder. I judge myself by my intentions. Others judge me by my actions. My intentions and

the actions that others see may be miles apart. Unless I know that, I am unlikely to change

my actions or try to get others to see me differently. I can become trapped in their reality and

get very frustrated when they don’t respond to me as I’d like. (Location No.1043)

This is what happened to Alicia; it hurt her to receive negative feedback and that had

negative effects on her overall performance as a manager. Once she realized that, she began to see

feedback from a different perspective and tried to listen to it, accept it, and learn from it. This was a

major step for her to see where she thought she was and what she was doing right and/or wrong, and

how others saw her and her actions.

Milestones and feedback include: the quality of her managerial/coaching ability, her personal

professional development, and business communication performance will be improved even more

when she begins the second training cycle of her corporate training program. Being exposed to

sophisticated professional material, studying case studies and relating them to her real business

settings, and formulating her knowledge and bringing it into application in her pragmatic

professional challenges, will help accelerate her progress.

Recommendations

To achieve effective managerial and coaching skills, protracted, unhindered, persistent

exposure to and application of the material and discussions with the coach are required. However,

the managerial system of an organization matters significantly. “Problems of organizational

behaviour and performance stem from a poorly designed and ineffectively managed system” (Beer,

Finnstrom, & Schrader, p. 55). Therefore, it is not enough to train and coach an employee,

“Changing that system to both support and demand new behaviours will enable learning and

improve effectiveness and performance” (p. 55). This process requires the determination of the

candidate as well. After all, it is challenging to subject oneself to a demanding organizational

environment, which consists of everlasting change, complexity, and human behavior that appears

incomprehensible at times. “So . . . The primary target for change and development is the

organization-followed by training for individuals” (p. 55).

Comprehending, being proactive, developing abilities, balancing work life with personal life,

is cumbersome: It requires constant consultation, patience, and intellectual ability. Likewise, trying

to manage people, may at many times hinder communication and the progression of projects and

tasks which can bring stress and frustration. “One powerful way to connect with your team members

is to get up and [sic] from your desk and talk to them, to work with them, to ask questions, and to

help when needed. This practice is called Management By Wandering Around, or MBWA” (Mind

Tools, 1996–2016). As with all challenges, managing and coaching people requires managerial self-

knowledge, determination, and commitment. No matter how much work is done in the coaching

sessions, if there is no self-motivated exposure to the tasks entailed, progress will inevitably stall.

The most important aspect of our work as corporate trainers and coaches is to offer the

bedrock of knowledge, plant the seed of motivation, and then keep “watering” this seed until it

blooms. That is why our sessions combine the intellectual with the instinctive: Managing and

coaching people, after all, is an intuitive thing, and should be treated as such.

Continuing coaching efforts will focus on development of other leadership competencies

such as:

• Continuation of improving peer group teamwork

• Delegating responsibility clearly

• Negotiating effectively

• Active Listening

• Behavioral change

• Briefings and meetings

The coaching can proceed after the 360-degree performance review is conducted and by reassessing

her target focus aligned with the company’s strategy and vision.

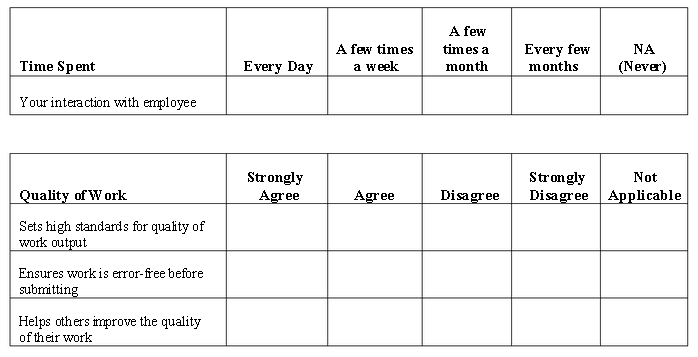

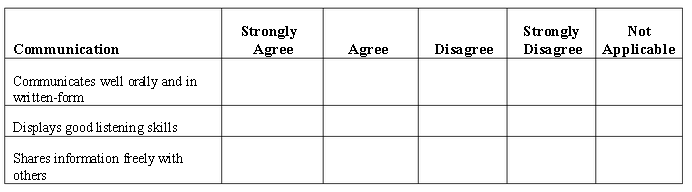

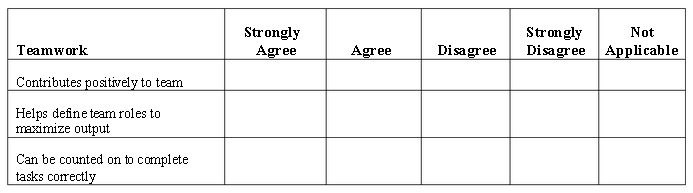

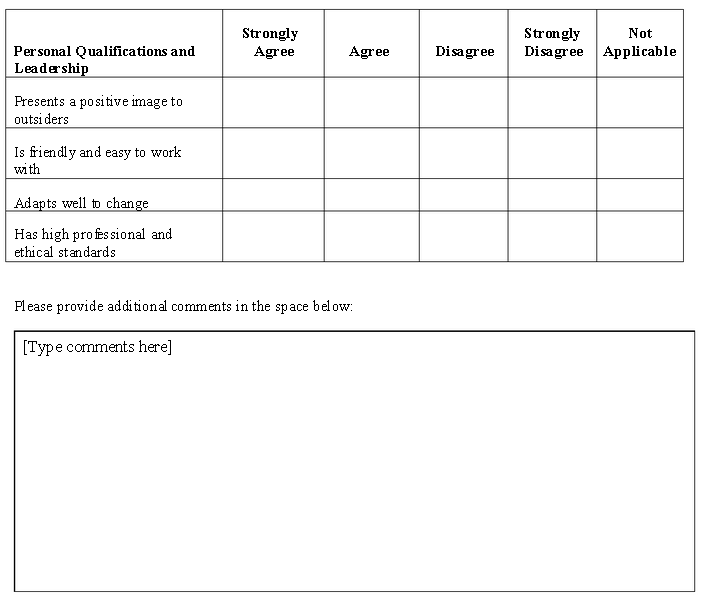

360-Degree Assessment

As aforementioned, a 360-degree performance appraisal was conducted at the end of the first

training cycle to determine if and how her business training and coaching had affected her leadership

and managerial style. The 360-degree performance evaluation form given to her colleagues can be

seen in Appendix III. Selected data from the 360-degree performance evaluation forms have been

summarized and provided in the subsequent section.

First, we must examine the benefits of 360-degree assessments. “It is becoming widely

recognized that 360-degree feedback offers several advantages over single-source assessment”

(Fleenor, 1997, p. 52). Since 360-degree assessments include feedback from a wider audience, e.g.,

colleagues, direct reports, upper level management, and so on, the perspectives vary and the result

gives a more realistic view of a person’s performance. An important benefit of multi-rater feedback

is that individuals are able to gain insight into how a particular audience evaluates their behavior and

perceives their competencies. Also, the use of this type of instrument can decrease some of the

biases and subjectivity that a single individual’s performance appraisal can generate. Fleenor and

Prince say: “Although it is true that all raters may be affected by biases, the use of more than one

perspective permits the ratings to be averaged across a number of respondents, which may provide a

truer evaluation of the focal manager’s performance” (p. 53). An additional advantage to a 360-

degree assessment is the insertion of self-assessment. Fleenor and Prince share “discrepancies

between self and others’ ratings can provide important insights about managerial and leadership

effectiveness” (p. 54). Gaining an understanding of the differences between the self-observation and

the view of the other organizational members is a vital step in identifying areas for leadership

development. Further, this data can help an individual in developing a more accurate self-

assessment, a trait of Self-Awareness – which is one of Goleman’s (2000) fundamental capabilities

of Emotional Intelligence. The feedback gathered from this assessment will prove pivotal in the

development of Alicia’s leadership and management skills and in combination with her corporate

development and coaching it will escalate her performance and improve the effectiveness of her

team.

Selected Data from Alicia Torres’ 360° Performance and Feedback Review – October 2016

Comments from direct managers and/or directors higher in the organization hierarchy:

Person A: She is passionate with her job. Will come out of her way to assist a client and/or a

colleague. She is a perfectionist and cares about the details. She is a great sales person and clients

like her a lot. She has improved her team communication skills since she began her corporate

training-coaching program. Listens more carefully and asks more clarifying questions. However, she

is too sensitive and gets very much influenced when something happens in the company. She often

thinks that everybody is talking about her or criticizing her. Sometimes I feel like she wants to be

pampered.

Person B: Alicia is very knowledgeable about her work. She has helped me in many ways

since I came to the company. Sometimes it’s hard to work with her because she ”assumes things,”

but lately she has been asking more questions before she comes to her own conclusions. Her team

meetings have improved also; they were monotonous (she would talk all the time), now she involves

her team members more into the discussions, asks more about their experiences and ideas; she

brainstorms more and tries to help her team come up with creative solutions. She has also been

trying to empower her reps more by assigning projects to them rather than her doing all the work

(she always thought she did everything better than everybody else).

Person C: Alicia has been very happy since she started her corporate training and coaching

sessions. She seems more promising and prosperous. She has all these new ideas and I think that she

believes in herself more now. She sometimes is too apologetic, though, and is very anxious of what

everybody else thinks of her. Maybe she needs to work a bit more on her people skills and start

coaching again.

Comments from direct reports lower in the organization hierarchy:

Person D: Alicia has changed a bit since she started her coaching program. She asks more

questions, she considers our ideas and gives us more responsibilities than before. I know she cares

about the company and us but sometimes I feel like she is my mother.

Person E: Our meetings have improved from being boring to a bit more interesting. I like

that she gave me a project that she always undertook, so I hope that means she trusts me more. In

general, she looks happier and it reflects when we go out to meet clients. She is such a good

saleswoman. I try to copy her style. I think we need to work more on our team bonding, but she has

been trying to engage us more.

Person F: She tries to listen to us and actually takes our ideas seriously. I thought she was

only interested in the numbers we bring to the company. She is trying to connect with us more than

before, but we have to get used to this new Alicia. It may work, I am not sure yet. I like our

brainstorming meetings because I get the chance to speak more than before and it makes me feel

more acknowledged. I can see a difference in the way she approaches us and it is for sure better now

than before.

Person G: Alicia is dynamic. She always was. She is devoted to our company and I respect

that. I know that she was promoted to sales manager because she was a star sales person. I am not

sure she has managerial knowledge but it seems to me that she is willing to learn and tries hard to

help us. I like working with her I am sure she will enhance her skills.

Comments from various colleagues and peers in the organization:

Person H: As a colleague Alicia has been polite and helpful. She has gone out of her way

many times to help others and me. Sometimes I think she says too many “yeses” to people and then

is drained and tired. Then she complains about it . . .

Person I: Alicia works in another division than me. However, we have collaborated in some

cases where our departments had joint projects. She was always willing to help and seems to be

devoted to our company. I think she is too good to others sometimes. In general, I have no problems

with her.

Person J: She complains to me sometimes that she doesn’t feel respected and acknowledged

for her efforts by her director and her CEO. It seems like she wants to gain their attention and is not

sure how. She is friendly with others and me though and is an ethical person. Change is not her best

friend and in general wants to feel secure before she goes on to something new. She seems ambitious

and I think she wants to go up the ladder.

Self-evaluation: I am a perfectionist with high standards, I am helpful with others and try to

listen more than before and delegate tasks effectively to my team. I sometimes overwork myself to

please everybody. I have passion for what I do and want to improve my business skills even more. I

believe that I have a great team and want to get out the best of them. It does seem overwhelming

sometimes. I hope I can do it.

Chapter 7: Findings

“We must be the change we wish to see in this world.”

(Clemmer, Location No. 1071)

Once the initial training cycle (cycle A) was completed and the 360-degree assessment

concluded, the literature of this study along with the weekly journals, and the 360-degree evaluation

results were studied and observed to report the findings of this research project. The primary

finding(s) was completely different from what the company, the trainee/coachee, and even the

trainer/coach had in mind when this case study commenced.

To begin with, it was observed, that although Alicia was an excellent trainee, was supported

via coaching, and was able to initiate some changes in her management and leadership style, there

were still many traits from her “old self” left to work on. She was able to change the way she once

managed her team by incorporating coaching-like approaches, like active listening, empowering her

people, asking powerful questions, giving and receiving genuine feedback, delegating effectively,

and so on. However, she continued to feel that she was criticized and not appreciated by her higher-

level executives. She still wanted to attract their attention by overworking herself in order to prove

what she was worth. She is still very sensitive to what others think of her and say about her, which

influences her ability to function efficiently, to think clearly without biases, and it lessens her

performance overall. So, although she is helpful with her people and colleagues and has gained

significant theoretical business knowledge from her initial state, via coaching, it was observed that

more needed to take place to change her leadership behavior. Thus, she was asked the following

question: “What is the major obstacle that prevents you from engaging a full, coach-like, leadership

approach behavior now that you have gained valuable business training, significant coaching

knowledge, and on-the-job live practice, of some of your new coach-like skills, and you saw that

whatever you have changed brought you success?” The answer to this question, after Alicia reflected

and thought about it a bit was: “That’s a good question! Now that I have been exposed to so much

theoretical business management, leadership, and coaching skills training, and I have seen how all

this has influenced me to improve, and without a doubt, I do believe that this is the most effective

leadership style of all that I have been exposed to in my career so far; however, it seems to be a bit

more challenging to me perhaps, maybe, because I feel that I am personally not receiving this kind

of leadership style from my peers above me. I feel as they are leading me via other

managerial/leadership styles, like a more authoritarian style or maybe as we learnt, via transactional

leadership style. I don’t feel they are there for me.”

This was the “aha” moment for Alicia. She now knew what she could do and not do. She

now knew that she needed the “same support” she was learning during her corporate training and

coaching sessions to be applied to her as well. She said that: “If I could be led under the same or

similar conditions, I feel my performance would boost so high and that it would help me, help my

team members, leverage the company’s sales results.”

According to Robbins, Judge, and Vohra (2012), Transformational leaders versus

Transactional leaders:

Inspire followers to transcend their self-interests for the good of the organization and have an

extraordinary effect on their followers . . . They pay attention to the concerns and needs of

individual followers; they change followers’ awareness of issues by helping them look at old

problems in new ways; and they excite and inspire followers to put out extra effort to achieve

group goals. (p. 409)

This is exactly what Dr. Hicks (2014) argues:

Without the ability to coach, it will be impossible to demonstrate one of the core components

of transformational leadership: Individualized Consideration . . . One way in which

transformational leaders personalize their relationships is to know people as individuals; their

desires, needs, and concerns. In the process, they pay attention to each person’s needs for

achievement and growth. New learning opportunities are created to help followers reach

successively higher levels of development. Through informal conversations, which

encourages two-way communication, and by listening effectively, transformational leaders

become familiar with how people are doing and when help is needed with problem situations.

As a result, they are seen as accessible and approachable for coaching and mentoring. For the

transformational leader, showing Individualized Consideration through helping conversations

is not a passive process, but one that is proactively practiced. (p. 21)

Therefore, although we have observed through this research project that coaching, as a leadership

style, is an effective approach of leading, empowering, developing people and leveraging their

potential, for it to be realistic and prosperous, it must be applied by senior management first. Wilson

(2004), discusses how he has:

Often noticed how you can tell what the CEO is like by talking to the receptionist, no matter

how many lines of management exist in between. If the receptionist is rude to you, chances

are there is a bully at the top. Every boss is a role model, consciously or otherwise, and some

of their attitudes will inevitably be reflected by the staff.” (p. 97)

He continues to say that, “everyone can change their management style” (p. 97), toward a coaching

culture approach, as long as they are provided with the necessary tools to do so; he argues that

besides learning and understanding the principles, the techniques need to be practiced “in real work

situations in order to become fluent.” Plenty of practice is needed “with the safety net of an

instructor by one’s side” (p. 97).

Moreover, according to Beer, Finnstrom, and Derek (2016):

Senior executives and their HR teams continue to pour money into training programs, year

after year, in an effort to trigger organizational change. But what they actually need is a new

way of thinking about learning and development. Context sets the stage for success of failure,

so it’s important to attend to organizational design and managerial processes first and then

support them with individual development tools such as coaching and classroom or online

education. (p. 52)

They continue by saying that there has been research conducted with such problems as early as the

1950s:

They found that one program succeeded in changing frontline supervisors’ attitudes about

how they should manage, but a follow-up study revealed that most supervisors had then

regressed to their pre-training views. The only exceptions were those whose bosses practiced

and believed in the new leadership style the program was designed to teach. (p. 52–53)

In conclusion, as we have seen from the various literature review and case study, coaching

can have many promising aspects to help improve leadership approaches and corporate culture.

However, for these tactics to be grounded and made part of the organizational corporate culture they

must be built within the companies’ foundations, starting from the top executive layers. The senior

leaders need to begin adopting the coaching approach leadership style, practice it actively, and lead

by example. As Clemmer, said, “Leaders don’t seek to change others, but to change themselves.

They become models of change for others” (Loc. 1071). The message of this quote can have a

dyadic approach to coaching as a leadership style in correlation to Alicia’s case study. Initially, as

discussed, it can suggest that Martha (CEO), and James (sales director) comprehend their personal

leadership styles, define them, assess them for their effectiveness, and amend them where and when

necessary to reflect the executive positions they currently hold in relation to their company’s

international leadership and management value pathway, (see appendix II). Secondly, it can create a

great opportunity for Alicia to learn and adopt some additional leadership competencies, which have

principles from coaching as a leadership style, and can help her comprehend how to “lead from the

middle of an organization,” and as Maxwell (2005), states, to become a “360-Degree Leader.” In his

book, “The 360° Leader: Developing Your Influence from Anywhere in the Organization,” he argues

that individuals do not need to reach the top of an organization to lead; they can lead effectively

from the middle levels of a corporation.Alicia, seems frustrated; she even considered leaving the

organization when she realized that she was led by ineffective leaders. Nonetheless, Alicia can

increase her chances of making a difference in her company and maybe even influence her leaders

above her by utilizing her new leaderships skills, acquired form her corporate training, by

employing Maxwell’s nine principles of leading−up. Maxwell claims:

Influencing your leader isn’t something you can make happen in a day. In fact, since you

have no control over the people above you on the organizational chart, they may refuse to be

influenced by you or anyone under their authority. So there’s a possibility that you may never

be able to lead up with them. But you can greatly increase the odds of success if you practice

the principles . . . Your underlying strategy should be to support your leader, add value to the

organization, and distinguish yourself from the rest of the pack by doing your work with

excellence. If you do these things consistently, then in time the leader above you may learn to

trust you, rely on you, and look to you for advice. With each step, your influence will

increase, and you will have more and more opportunities to lead up. (p. 83)

According to Maxwell, the nine principles 360−degree leaders need to lead up, are:

1. Lead yourself exceptionally well.

2. Lighten your leader’s load.

3. Be willing to do what others won’t.

4. Do more than manage−lead!

5. Invest in relational chemistry.

6. Be prepared every time you take your leader’s time.

7. Know when to push and when to back off.

8. Become a go-to player.

9. Be better tomorrow than you are today. (p.157)

The international corporate realm has witnessed many cases like Alicia’s, Manfred F. R. Kets de

Vries (2016), in his article, “Managing Yourself: Do You Hate Your Boss?” says that Stacy, who

worked at a top tech company, loved her job,

Until her boss left for another firm. The new manager, Peter, seemed to dislike pretty much

everyone on the team he had inherited . . . He was aloof, prone to micromanaging, and apt to

write off any project that wasn’t his brainchild.” (p. 98)

Stacy was not able to escape the situation with Peter, which made her feel “stressed, depressed, and

increasingly unable to do good work. She worried that the only way out was to leave the company

she loved” (p. 98). Thus, Stacy and Alicia both viewed their situations as an anathema, which

unfortunately, is not uncommon. Kets de Vries (2016), states that a recent study conducted by

Gallup, “State of the Global Workplace,” found that “half of all employees in the United States have

quit jobs at some point in their careers in order to get away from their bosses” (p. 98). Kets de Vries

gives several opinions on how this predicament can be confronted. In one of his views he says that

the preliminary approach is practicing empathy and considering “the external pressures your

manager is under . . . Most bad bosses are not inherently bad people; they’re good people with

weaknesses that can be exacerbated by the pressure to lead and deliver results” (p. 99). He believes

that empathy can create a significant shift “in difficult boss-subordinate relationships, and not just as

a top-down phenomenon” (p. 99). He discusses the importance “of emotional intelligence to manage

up,” and argues that, “Neuroscience also suggests that it’s an effective strategy, since mirror neurons

in the human brain naturally prompt people to reciprocate behaviors” (p. 99). Hence, he concludes

by saying that if employees work on understanding and empathizing with their managers, it is likely

that they will begin mimicking their empathizing behavior. This behavioral modification can have

tremendous beneficial effects on all organizational stuff.

Consequently, for coaching as a leadership style to be implemented successfully, it must be

embodied within the roots of the corporation itself and spread its seeds from its “head” to its “toes”;

and as Maxwell discusses, from the middle of the organization to the top. Moreover, extending

Maxwell’s premise, change might also occur from the “toes” of the organization to its “head”, not

just from the middle. This way, the results can be concrete, supported, sustained, and applied as part

of its organizational strategy, culture, and leadership value pathway by all its organizational

members.

References

Austin, J. (2013). The humble and the humbled: A grounded theory of humility in organizational

leadership (Doctoral dissertation). Retrieved from

http://researchportal.coachfederation.org/MediaStream/PartialView?documentId=2662

Beer, M., Finnstrom, M., & Schrader, D. (2016, October). Why leadership training fails-and what to

do about it. Harvard Business Review, 50–57.

Bungay, M. S. (2016). The coaching habit: Say less, ask more & change the way you lead forever.

Toronto, Canada: Box of Crayons Press [Kindle for iPad edition]. Retrieved from

Amazon.com

Cappelli, P., Singh, H., Singh, J. V., & Useem, M. (2010, March). Leadership lessons from India.

Harvard Business Review, 1–9.

Clemmer, J. (1999). Growing the distance: Timeless principles for personal, career, and family

success. Canada: TCG Press [Kindle for iPad edition]. Retrieved from Amazon.com

Fleenor, J., & Prince, M. (1997). Using 360-degree feedback in organizations:

An annotated bibliography. Greensboro, NC: Center for Creative Leadership.

Goleman, D. (2000, Mar.–Ap.). Leadership that gets results. Harvard Business Review, 78–91.

Goleman, D., Boyatzis, R., & McKee, A. (2001, Dec.). Primal leadership: The hidden driver of great

performance. Harvard Business Review, 32–43.

Groysberg, B., & Lee, L. E. (2008, July–Aug.). Employee motivation: A powerful model. Harvard

Business Review, 78–84.

Harvard Business Review. (2016, Sept.). Why people quit their jobs. Harvard Business Review, 20

Hicks, R. F. (2014). Coaching as a leadership style. New York, NY: Routledge.

Kets de Vries, M. F. R. (2014, Ap.). Coaching the toxic leader. Harvard Business Review, 100–109.

Kets de Vries, M. F. R. (2016, Dec.). Managing yourself: Do you hate your boss? Harvard Business

Review, 98–101.

Kite, N., & Kay, F. (2012). Understanding emotional intelligence. London and New York: Kogan

Page Limited. Retrieved from

http://proquest.safaribooksonline.com.libproxy.utdallas.edu/book/personal-

development/9780749458805/01-emotional-intelligence-explained-and-

illustrated/01_emotional_intelligence_expl

Koch, C. (2006). The new science of change. CIO Magazine. Retrieved from

http://www.lexisnexis.com.libproxy.utdallas.edu/Inacui2api/

Kotter, J. P. (2001, Dec.). What leaders really do. Harvard Business Review, 85–96.

Maxwell, J. C. (2005). The 360° leader: Developing your influence from anywhere in the

organization. Nashville, TN: Thomas Nelson Business.

Mind Tools. (1996–2016). Management by wandering around (MBWA): Staying in touch with your

team. Retrieved from https://www.mindtools.com/pages/article/newTMM_72.htm

O’Neil, M. B. (2007). Executive coaching with backbone and heart. San Francisco, CA: Jossey-

Bass, a Wiley Imprint.

Peltier, B. (2010). The psychology of executive coaching. New York, NY: Routledge Taylor &

Francis Group.

Robbins, S. P., Judge, T. A., & Vohra, N. (2011). Organizational behavior (15th ed.). New Delhi:

Pears

Rock, D., & Donde, R. (2008). Driving organizational change with internal coaching programs: Part

one. Industrial and Commercial Training, 40(1), 10–18. Retrieved from

http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00197850810841594

Stober, D. R., & Grant, A. M. (Eds.). (2006). Evidence based coaching handbook. Hoboken, NJ:

John Wiley & Sons, Inc.

Underhill, B. O., McAnally, K., & Koriath, J. J. (2007). Executive coaching for results. San

Francisco, CA: Berrett-Koehler Publications, Inc.

Waldroop, J., & Butler, T. (1996, Nov.–Dec.). The executive as coach. Harvard Business Review,

111–117.

Wilson, C. (2004). Coaching and coach training in the workplace. Industrial and commercial

training, 36(3), 96–98. Retrieved from http://dx.doi.org/10.1108/00197850410532087

Yin, R. K. (2015). Qualitative research from start to finish (2nd ed.). New York, NY: The Guilford

Press. Retrieved from

http://site.ebrary.com.libproxy.utdallas.edu/lib/utdallas/detail.action?docID=11069040

Yin, R. K. (2014). Case study research: Design and methods, (5th ed.). Thousand Oaks, CA: Sage

Publications Ltd.

on Education.

Appendix I. Medical Division Organizational Chart

Appendix II: Overall Managerial and Leadership Ideology of the Organization

The company has a common international leadership and management value pathway. This

company trains its executives and managers to lead with the following values and mindset. Some of

its main values and attributes of leading include:

• Committed to a promising future

• Being open to new learnings and help others learn

• Bring results

• Empower and develop others

• Accountability

• Self assessment

• Respect & honesty

• Commitment to goals

• Leading as a coach

• Listening generously

• Action and feedback

• Move forward

• Overcoming barriers

• Engaging others